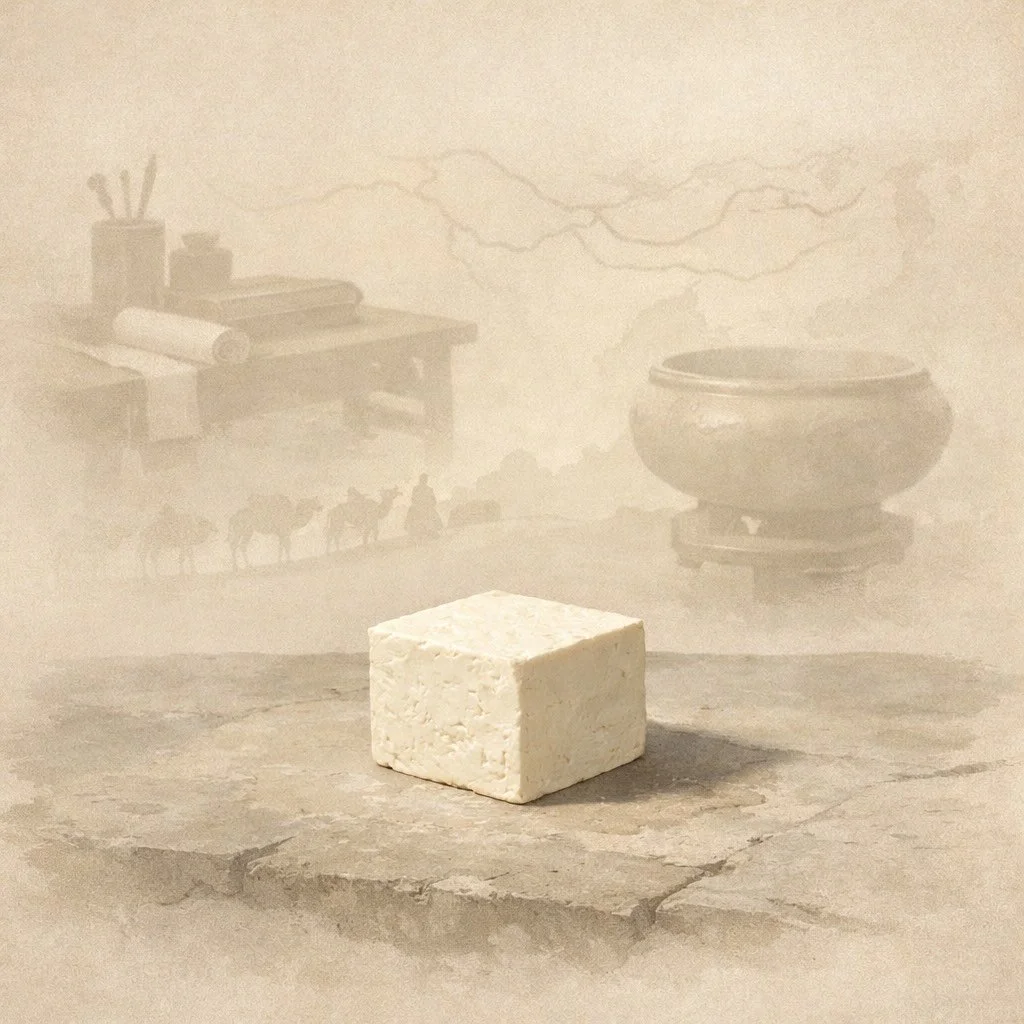

How Tofu Shaped Ancient Cultures: Trade, Health and Spirit

Introduction: More Than Food

Tofu is often framed as a modern invention—an answer to contemporary questions about health, sustainability, and ethics.

But tofu is far older than our current debates.

For over a millennium, tofu quietly shaped ancient societies. It fed monks and scholars, crossed borders through trade, and earned a place in medical texts and spiritual rituals. Long before it was labelled plant-based, tofu was already solving real human needs: nourishment without excess, protein without harm, and food aligned with philosophy.

Understanding tofu’s cultural past helps explain why it continues to endure—not as a trend, but as a civilisational food.

Origins in Imperial China: Innovation Meets Philosophy

Most historical records trace tofu’s origin to China, likely during the Han Dynasty (circa 2nd century BCE). While the exact inventor remains debated, tofu emerged from a sophisticated understanding of soy processing—grinding, heating, coagulating, and pressing soy milk into a stable, nourishing form.

What mattered was not just how tofu was made, but why it was valued.

Chinese philosophy emphasised balance:

Yin and yang

Nourishment without excess

Food as medicine

Tofu fits perfectly. It was soft yet sustaining, cooling yet strengthening, modest yet complete. This alignment with Daoist and Confucian thinking helped tofu move beyond novelty and into daily life.

Tofu as Medicine: Food in the Classical Pharmacopoeia

By the Song and Ming dynasties, tofu appeared in Chinese medical literature—not as a cure-all, but as a therapeutic food.

Classical physicians described tofu as:

Cooling in nature

Moistening to dryness

Gentle on digestion

Supportive to the spleen and stomach

Unlike meat, tofu was believed to nourish without burdening the body. This made it ideal for scholars, elders, and those recovering from illness.

In an era without refrigeration or supplements, tofu provided reliable protein in a form that aligned with long-term health—not short-term indulgence.

Trade Routes and Cultural Exchange

As soybeans travelled along trade routes, so did tofu-making knowledge. Buddhist monks, merchants, and diplomats carried both the ingredient and the technique across East Asia.

Tofu spread into:

Korea, where it was integrated into temple cuisine

Japan, where it evolved into highly refined forms

Vietnam, where it absorbed local herbs and broths

Unlike preserved meats or luxury spices, tofu adapted easily. It could be made fresh anywhere soybeans and water were available, making it a decentralised, democratic food.

Spiritual Discipline and Buddhist Temples

Tofu’s deepest cultural roots may lie in spiritual practice.

Buddhist monastic traditions across China, Korea, and Japan required foods that aligned with ahimsa—the principle of non-harm. Meat was excluded, but monks still needed strength for long hours of meditation, study, and labour.

Tofu became essential.

In Japanese Zen temples, tofu was elevated to an art form—treated with reverence, precision, and restraint. Dishes were designed to express impermanence, simplicity, and respect for ingredients.

Eating tofu was not about replacement. It was about presence.

A Food of the People

Beyond temples and scholars, tofu became a cornerstone of everyday life.

For farmers and working families, tofu offered:

Affordable protein

Minimal fuel requirements

Local production

Shared community labour

Village tofu makers often served entire neighbourhoods. Fresh tofu was bought daily, cooked simply, and eaten together.

In this way, tofu was not just nourishment—it was social infrastructure.

Why This History Still Matters

Modern conversations about tofu often focus on macros, emissions, or trends. But tofu’s resilience comes from something deeper.

For centuries, tofu endured because it respected limits:

Ecological limits

Bodily limits

Ethical limits

It asked less of the land and less of the body, while giving enough.

Final Takeaway: A Quiet Legacy

Tofu did not conquer cultures through force or luxury.

It endured through humility.

It fed monks seeking clarity, scholars seeking balance, and families seeking survival. Across centuries, tofu proved that nourishment does not need excess, and progress does not need harm.

When we choose tofu today, we are not adopting something new.

We are continuing a long, thoughtful conversation between food, culture, and care.

Sometimes, the most powerful foods whisper rather than shout.