Korean Temple Cuisine: Harmony, Simplicity, and Umami

A Cuisine Shaped by Mindfulness

Korean temple cuisine is inseparable from the philosophy of Korean Buddhism. Developed and preserved in mountain monasteries across South Korea, this cuisine is less about indulgence and more about awareness of seasons, ingredients, and the self.

Meals are prepared and eaten as an extension of meditation. Every chop, soak, and simmer is intentional. Food is not meant to excite the senses aggressively, but to steady them.

This approach aligns closely with the ethos of Tofu World: gentle nourishment, respect for ingredients, and meaningful change through everyday meals.

The Rule of Five: What Is (and Isn’t) Used

Temple cuisine follows a strict guideline known as obangsaek (the five colours) and osinchae (the five pungent vegetables).

Excluded ingredients

Garlic

Onions

Chives

Leeks

Scallions

These aromatics are believed to overstimulate the mind and disturb calm.

Embraced ingredients

Mountain greens (namul)

Wild roots and shoots

Soybeans (tofu, doenjang, ganjang)

Mushrooms, seaweed, sesame

Seasonal vegetables, lightly seasoned

Without garlic or onion, flavour must come from structure, fermentation, and natural glutamates—a masterclass in quiet umami.

Fermentation as the Heartbeat

If there is one place where Korean temple cuisine speaks directly to tofu lovers, it is fermentation.

Monks traditionally make their own:

Doenjang (soybean paste)

Ganjang (soy sauce)

Gochujang (often temple-adapted, without garlic)

These are aged for years, sometimes decades, developing deep savouriness without heaviness. The umami here is slow and layered—never sharp.

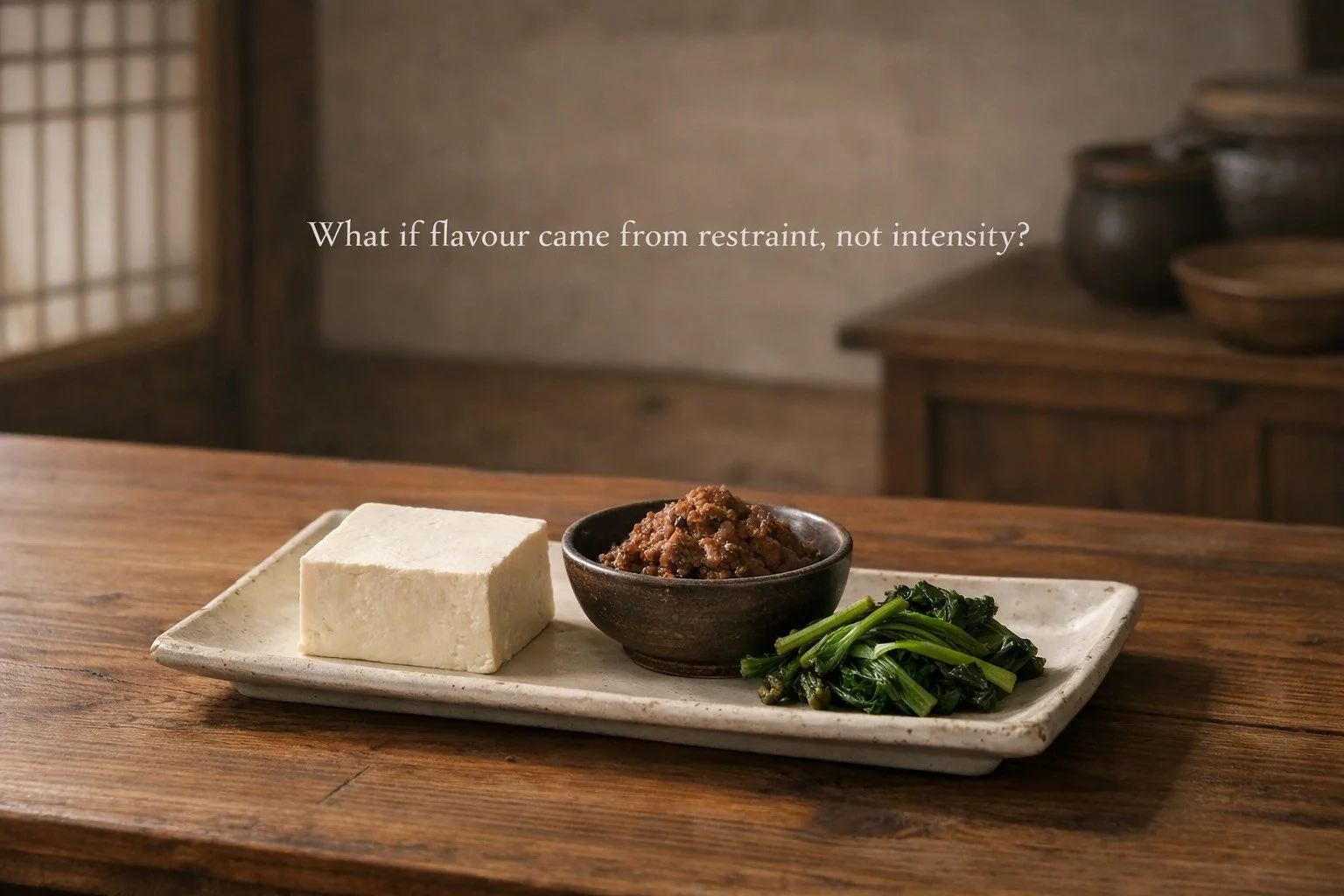

Tofu often appears simply:

Gently simmered in clear broth

Pan-seared and dressed with aged soy sauce

Paired with sesame oil and mountain greens

It’s not a meat replacement. It’s a protein with dignity.

Texture Over Intensity

Temple cuisine is subtle but never boring. Interest comes from contrast:

Soft tofu against chewy fernbrake

Slippery bellflower root with toasted sesame

Crisp lotus root beside tender soy curd

Cooking methods are restrained—blanching, steaming, slow simmering—allowing each ingredient to speak clearly.

This is an important lesson for modern plant-based cooking: you don’t need louder flavours, you need better listening.

A Living Tradition, Not a Museum Piece

While rooted in centuries-old practice, temple cuisine is not frozen in time. Figures like Jeong Kwan have introduced it to the global stage, showing that restraint and depth can coexist with contemporary kitchens.

Yet at its core, the cuisine remains humble. No plating tricks. No excess. Just nourishment.

In many ways, it offers an antidote to hyper-processed vegan food—reminding us that plant-based eating can be grounding, cultural, and deeply satisfying without imitation or excess.

What Tofu World Learns from Temple Cuisine

Korean temple cuisine reinforces several principles we hold dear:

Tofu is enough when treated with care

Umami doesn’t require additives—time and fermentation do the work

Simplicity is not a lack, but a refinement

Food can nourish both body and attention

For those exploring tofu not just as an ingredient, but as a philosophy, temple cuisine offers profound inspiration.

A Quiet Takeaway

Korean temple cuisine doesn’t ask you to eat differently overnight.

It simply invites you to slow down.

To notice the season.

To respect the soybean.

To let umami unfold gently.

And perhaps, in doing so, to discover that a kinder, calmer way of eating has been waiting all along—right there on the plate. 🌱