Daikon Radish: Crisp, Cooling and Far More Than a Garnish

Introduction 🌱

In Japan, Korea, and China, daikon has long been a staple—quietly capable rather than flashy. Raw, it’s crisp and peppery; simmered, it turns tender and almost pillowy; pickled, it cuts through richness like sunshine. And here’s the twist most people miss: the leaves are the nutritional headline, not the root.

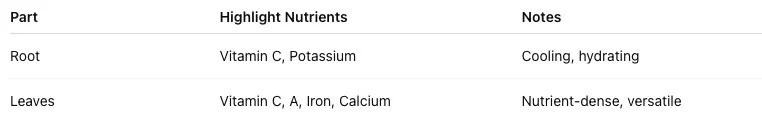

Nutritional Snapshot (Root vs Leaves) 🔬

Root: Low in calories, hydrating, and a good source of vitamin C and potassium.

Leaves: The real surprise? The leaves pack about double the vitamin C of the root—putting them almost on par with oranges—plus they’re also a source of vitamin A, iron, and calcium. Treat them as a leafy vegetable in their own right.

Quick Nutrition Comparison

Eat the greens! Sauté, blitz into pesto, add to soups, or dry for furikake.

Health Note: Raw vs Cooked (and Why It Matters)

Daikon’s digestive reputation comes from heat-sensitive enzymes (amylase, protease, lipase) and protective compounds called isothiocyanates (the same family found in broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables). These break down at relatively low cooking temperatures.

For digestive benefits: enjoy daikon raw (grated, slaws, salads).

For comfort and flavour absorption: cook it—accepting that the enzymes and isothiocyanates are reduced, but the texture becomes velvety and deeply satisfying.

🔍 Myth vs Truth: Daikon Edition

Myth: “Daikon is healthiest when cooked into soups and stews.”

Truth: Cooking creates tenderness and savoury depth, but destroys the enzymes and reduces isothiocyanates. For digestive perks, keep a raw side dish.

Myth: “The root is the most nutritious part.”

Truth: The leaves are nutritionally superior, with more vitamin C, plus vitamin A, calcium, and iron. The root offers texture and hydration, but the greens are the powerhouse.

The Peeling Question: Flavour vs Nutrition

Traditional advice recommends peeling 3–4 mm deep (or peeling twice) to remove fibrous bitterness and achieve a smoother bite.

But here’s the trade-off:

Deep peeling = smoother texture, less bitterness.

Light peeling or scrubbing = preserves nutrients, since many isothiocyanates and antioxidants sit just under the skin.

👉 The choice is yours: peel deeply for flavour refinement, or keep it light to maximise health benefits.

A Deeper Cultural Story 🥢

Japan: During the Edo period, daikon was a famine-saving crop—hardy, fast-growing, and storable. Later, it appeared in military rations to help replenish salt. Today, thick oden slices symbolise winter comfort, while snowy daikon oroshi refreshes grilled foods.

Korea: From fiery kkakdugi to broth-sweetening slices, daikon is a balancing food. In traditional medicine, it’s valued for its cooling effect against “heat” from fried or fatty meals.

China: Daikon “turnip cake” is a dim sum staple, and quick pickles cut through heavier meats.

Spiritual & agricultural role: Offered in Buddhist rites, and used as a “green manure” crop to enrich and heal soils.

Buy, Store, Prep: Precision that Pays

Buying: Firm, heavy roots; perky leaves if attached.

Storage: Roots last in the fridge up to 2 weeks; leaves just 2–3 days unless blanched/frozen.

Peeling: Choose your style → deep for smoothness, light for maximum nutrients.

Reducing sharpness:

Salt soak: 10–15 min, rinse.

Hot water blanch: 1–2 min.

Rice-wash water simmer: 3–5 min (traditional Japanese trick).

How to Use Daikon (and What You’re Optimising For)

Raw (enzymes & nutrients): grated daikon oroshi, crisp slaws.

Pickled: quick tang for bowls, wraps, or bánh mì.

Simmered: broth-soaked, tender, and comforting.

Stir-fried: fast, savoury side with tofu or mushrooms.

Leaves: sauté with garlic, stir into soups, or turn into furikake.

Perfect Partners: Daikon × Tofu

Contrast: Daikon’s crisp freshness vs tofu’s creaminess.

Pairings:

Tofu katsu topped with daikon oroshi.

Miso-simmered tofu & daikon in broth.

Rice bowls with pickled daikon and pan-seared tofu.

Mini Recipes

1) Crispy Tofu with Daikon Oroshi & Ponzu (Raw) – 20 min

Grate daikon, lightly squeeze.

Press, cube, dust tofu in cornstarch; pan-fry until golden.

Top with daikon, drizzle ponzu, and add spring onion + sesame.

2) Miso-Simmered Daikon & Tofu (Cooked) – 35 min

Peel lightly or deeply (see note), cut rounds, par-simmer 10 min.

Simmer in broth 12–15 min until tender.

Add tofu cubes; warm through.

Stir miso into broth off-heat; finish with daikon greens.

Common Mistakes (and Fixes)

Cooking for enzyme benefits. ❌ Enzymes are lost. ✅ Keep a raw element.

Thin peeling when aiming for smoothness. ❌ Still bitter. ✅ Peel deep for taste—or light if nutrients matter more.

Overcooking. ❌ Mushy. ✅ Aim for tender, not collapsed.

Ignoring leaves. ❌ Wasted nutrition. ✅ Use them as super-greens.

Daikon FAQ ❓🌱

Q1. Can you eat daikon raw every day?

Yes — daikon is often enjoyed raw in salads, slaws, and as grated daikon oroshi.

Q2. What do daikon leaves taste like?

They’re slightly peppery, like a cross between mustard greens and kale. Cooked, they mellow into a nutty, savoury green.

Q3. Is Korean mu the same as Japanese daikon?

They’re close relatives but not identical. Mu is shorter, rounder, and denser; Japanese daikon is longer, slender, and slightly milder.

Q4. How do people usually check if daikon is fresh?

In everyday cooking, many look for daikon that feels firm and heavy with smooth skin, and for leaves (if attached) that appear bright and fresh. These are common kitchen cues for peak quality.

Q5. Can you eat daikon skin?

Yes, though it can be fibrous and bitter. For smoothness, peel deeply; for nutrition, peel lightly or scrub.

Final Takeaway 💡

Daikon is three foods in one: root for crunch and comfort, leaves for powerhouse nutrition, and raw prep for digestive perks. Combined with tofu, it delivers freshness, calm, and quiet strength. More than garnish—it’s survival, history, and health on your plate.