The Science of Tofu: How Soybeans Become Culinary Gold

Why Tofu Feels Like Alchemy (But Isn’t)

To many cooks, tofu feels unpredictable. Sometimes it’s silky and calm. Other times it crumbles, weeps, or refuses to brown.

That uncertainty comes from one thing: tofu is rarely explained as a system.

Tofu isn’t just an ingredient—it’s a structure built from protein, water, heat, and minerals. When you understand how those elements interact, tofu stops feeling fragile and starts feeling dependable.

This is the science that turns soybeans into culinary gold.

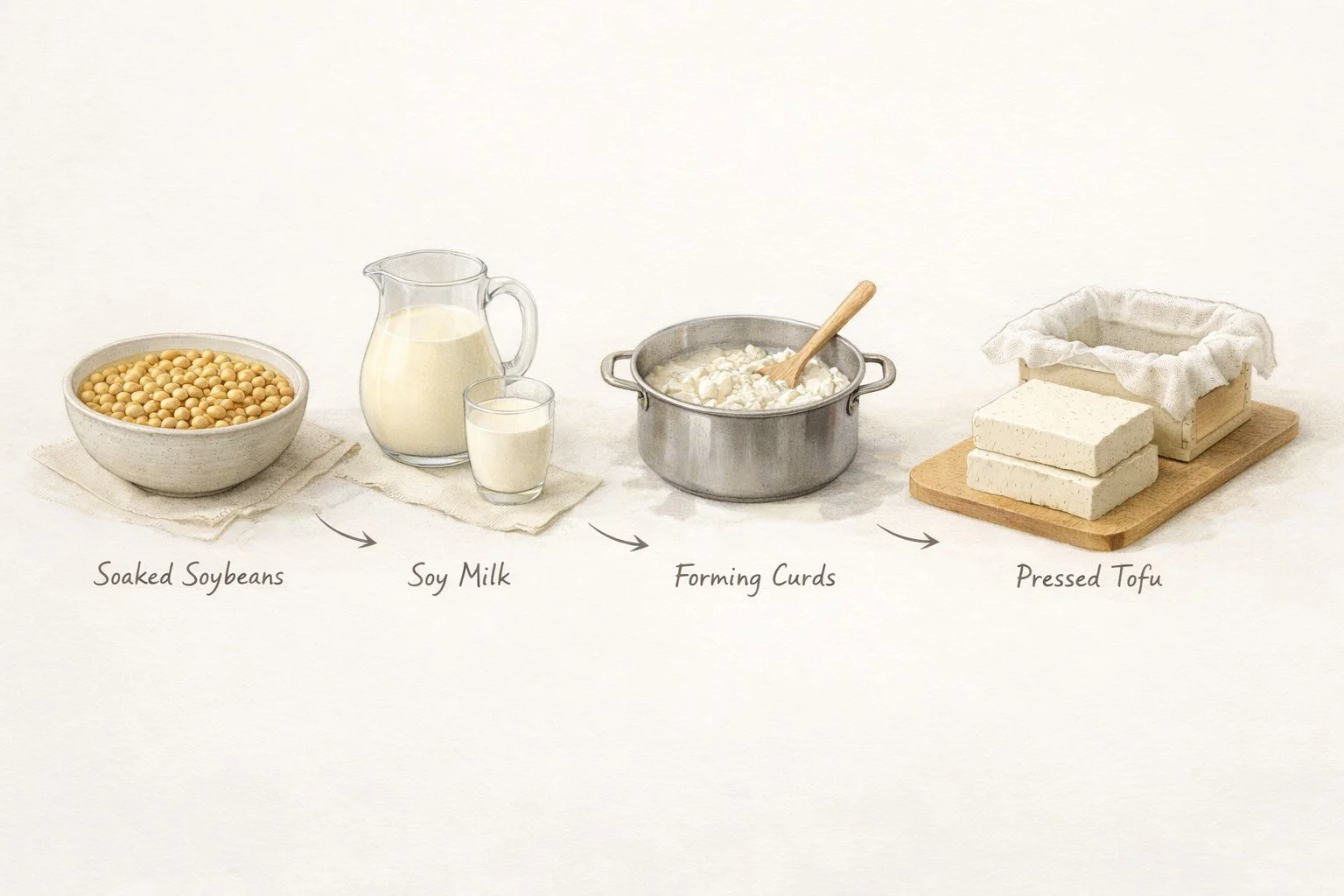

Step 1: Soybeans – Small Seeds, Big Proteins

Soybeans are unusually rich in complete protein, meaning they contain all nine essential amino acids. But those proteins are tightly folded and locked inside the bean.

The first job of tofu-making is to unlock them.

What soaking really does

Rehydrates the bean

Softens cell walls

Prepares proteins to unfold under heat

Without proper soaking, protein extraction is incomplete—and weak tofu is the result.

Step 2: Soy Milk – Protein in Suspension

Soaked soybeans are ground with water, then heated and strained. What you get is soy milk—not as a beverage, but as a protein suspension.

At this stage:

Proteins are dispersed in water

Fat is emulsified

Nothing is solid yet

This matters because tofu is not formed by drying—it’s formed by coagulation.

Step 3: Coagulation – The Moment Tofu Is Born

This is the defining moment.

When a coagulant is added, soy proteins denature and bond, forming curds that trap water inside a delicate protein network.

Common coagulants include:

Calcium sulfate (gypsum) – creates firm, clean curds

Magnesium chloride (nigari) – produces tender, slightly sweet tofu

Glucono delta-lactone (GDL) – yields ultra-smooth, custard-like textures

The choice of coagulant doesn’t just affect firmness—it shapes flavour, mouthfeel, and behaviour under heat.

Step 4: Pressing – Designing Texture

Once curds form, they’re gently gathered and pressed. This step controls how much water remains trapped in the protein network.

Think of tofu on a spectrum:

Silken tofu: barely pressed, water held loosely

Medium tofu: balanced protein–water ratio

Firm tofu: dense network, less free moisture

Pressing isn’t about removing flavour—it’s about engineering structure.

This is why tofu behaves differently when pan-fried, grilled, or simmered.

Why Tofu Reacts So Strongly to Heat

Tofu doesn’t brown like meat because it contains less sugar and no myoglobin. Instead, its reactions are governed by:

Surface moisture (too wet = steaming, not browning)

Protein density (denser tofu browns more predictably)

Oil contact (oil transfers heat; it doesn’t penetrate)

Once surface water evaporates, tofu can undergo the Maillard reaction, producing nutty, savoury notes.

Texture issues aren’t tofu problems—they’re physics problems.

The Hidden Elegance of Tofu

What makes tofu remarkable isn’t that it imitates anything.

It’s that:

It absorbs flavour without losing identity

It adapts to cultures, climates, and cuisines

It turns restraint into strength

From ancient Chinese kitchens to modern plant-based plates, tofu has endured because its structure is honest—and its science is sound.

Final Takeaway 🌱

Tofu isn’t bland.

It’s precise.

When you understand how soybeans become tofu—how protein sets, how water behaves, how structure forms—you stop fighting it.

And when you stop fighting tofu, it stops disappointing you.

That’s not magic.

That’s science—quietly working in your favour.