The Tofu Story: From Ancient China to Samurai Japan

From China’s Han dynasty to Japanese temples and courts, tofu’s journey is a story of refinement, philosophy, and artistry.

When we imagine food revolutions, we often think of flamboyant courts and exotic imports changing cuisines overnight. Tofu’s rise was far quieter—emerging in China over 2,000 years ago and travelling with Buddhism to Japan, where monks, warriors, and aristocrats shaped it into a cultural cornerstone.

From China to Japan: The True Origins

Tofu was likely first developed in the Han dynasty of China (often credited to Prince Liu An). By the Nara period (710–794 AD), it had reached Japan, carried alongside Buddhism. The earliest Japanese record of tofu dates to 965 AD in an official court document.

The 14th century was not tofu’s “origin” but rather the point when it became more widespread in Japan, moving from temples into everyday kitchens, aristocratic dining, and eventually the broader culture.

A Sacred Food in Buddhist Temples

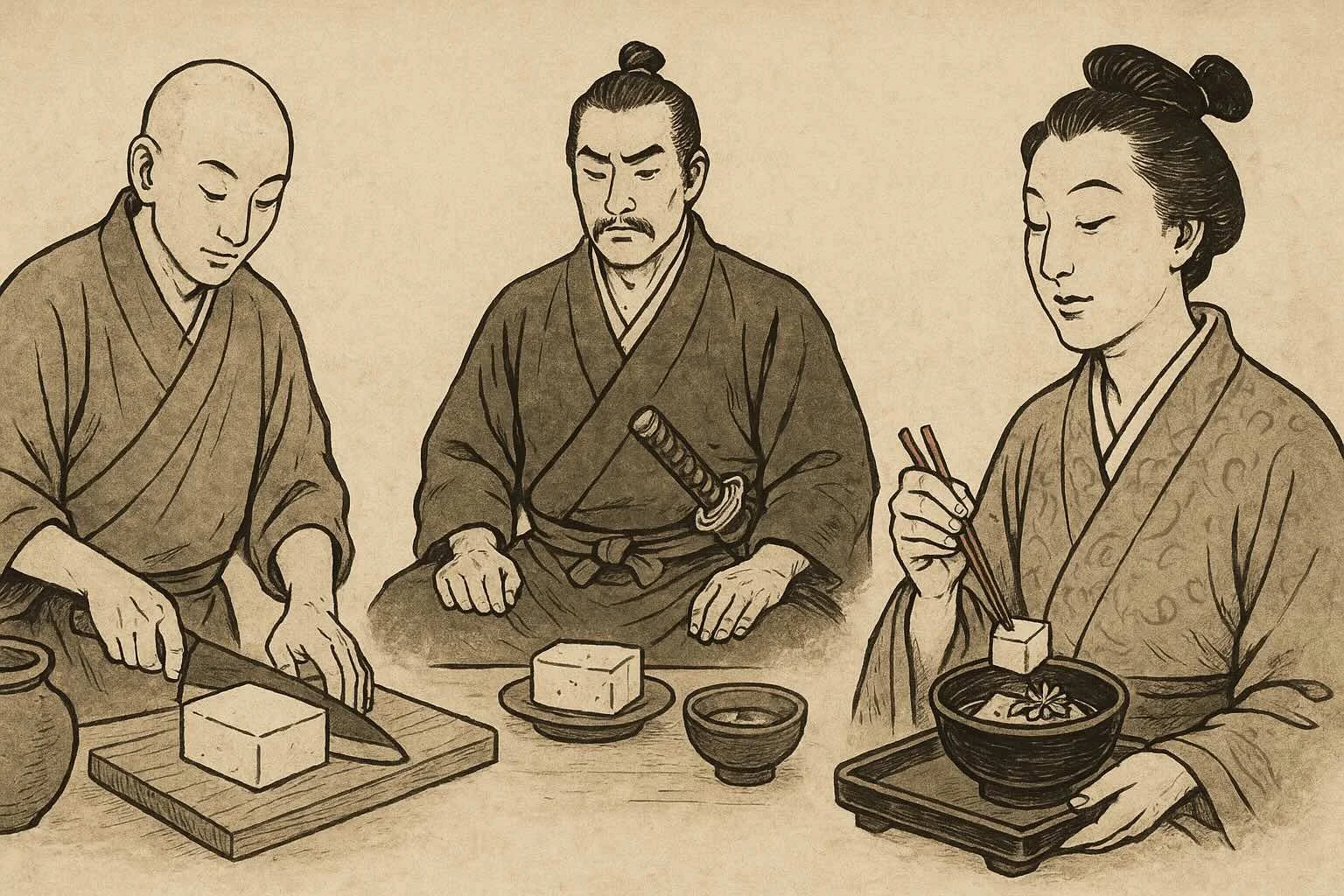

For Zen Buddhist monks, tofu was more than food—it was part of shōjin ryōri, temple cuisine grounded in discipline and mindfulness.

Meals followed guiding principles: harmony of colour, balance of taste, avoidance of pungent ingredients like garlic, and deep respect for seasonal produce. Tofu fit perfectly: subtle in flavour, endlessly adaptable, and spiritually “pure.”

Making tofu itself was treated as a meditative act. The careful soaking, grinding, and curdling of soybeans reflected the Buddhist pursuit of patience, focus, and respect for natural ingredients.

The Samurai’s Philosophical Diet

By the Edo period (1603–1868), samurai lived in an era of relative peace. Their diet was not forged on battlefields but shaped by Zen and Confucian values that emphasised balance and discipline.

The framework of ichijū-sansai—one soup and three dishes—anchored their meals. Tofu provided reliable protein within this restrained philosophy, supporting endurance and clarity of mind.

This was not food for indulgence but nourishment as practice. Tofu helped sustain both body and spirit, aligning with the warrior’s pursuit of discipline and self-control.

Aristocratic Banquets and Culinary Artistry

In aristocratic circles, tofu carried prestige. At times, laws even restricted its production to the upper classes. Its cultural value lay not in rarity, but in the artistry of its preparation and presentation.

Aristocratic chefs transformed tofu into elegant dishes, elevating simple seasonal ingredients into banquets that foreshadowed modern kaiseki cuisine. Kyoto’s pristine water became legendary for producing exceptionally smooth tofu, cementing the city’s reputation as a tofu capital.

Here, tofu symbolised refinement: a humble bean curd elevated by human creativity and skill.

Tofu’s First Mentions in Europe

While Portuguese missionaries helped introduce frying techniques like tempura to Japan, they were not the first Europeans to document tofu.

The earliest known record came in 1613, when British Captain John Saris described a Japanese “cheese made of beans.” Later, in 1665, Italian friar Domingo Navarrete used the term “Teu Fu” in his writings on Chinese cuisine.

These early mentions didn’t bring tofu into European kitchens overnight—but they marked the start of its slow entry into the global imagination.

From Local Staple to Global Icon

Today, tofu is everywhere: in stir-fries, fine dining, vegan burgers, and supermarket fridges around the world. Yet each block carries centuries of refinement:

Monks who saw tofu as food for clarity and mindfulness.

Samurai who ate it within a philosophy of discipline and balance.

Aristocrats who elevated it into an art form.

Common households that wove tofu into their daily meals, ensuring it was never only a food of elites but a shared part of Japan’s evolving cuisine.

Tofu’s story is not about sudden invention, but about quiet persistence and cultural dialogue. From its Chinese roots to Japanese artistry to global kitchens, tofu shows how the simplest foods can reshape history.

Final Takeaway 🌱

Every time you slice a block of tofu, you’re holding centuries of philosophy, patience, and creativity. What began as a humble soybean curd became a canvas for culture—monks meditating, warriors training, chefs elevating, families nourishing.

Tofu reminds us that food doesn’t need spectacle to change the world. Sometimes, the quietest revolutions last the longest.