From Bean to Block: The Traditional Art of Tofu Making

Tofu Was Never Meant to Be Anonymous

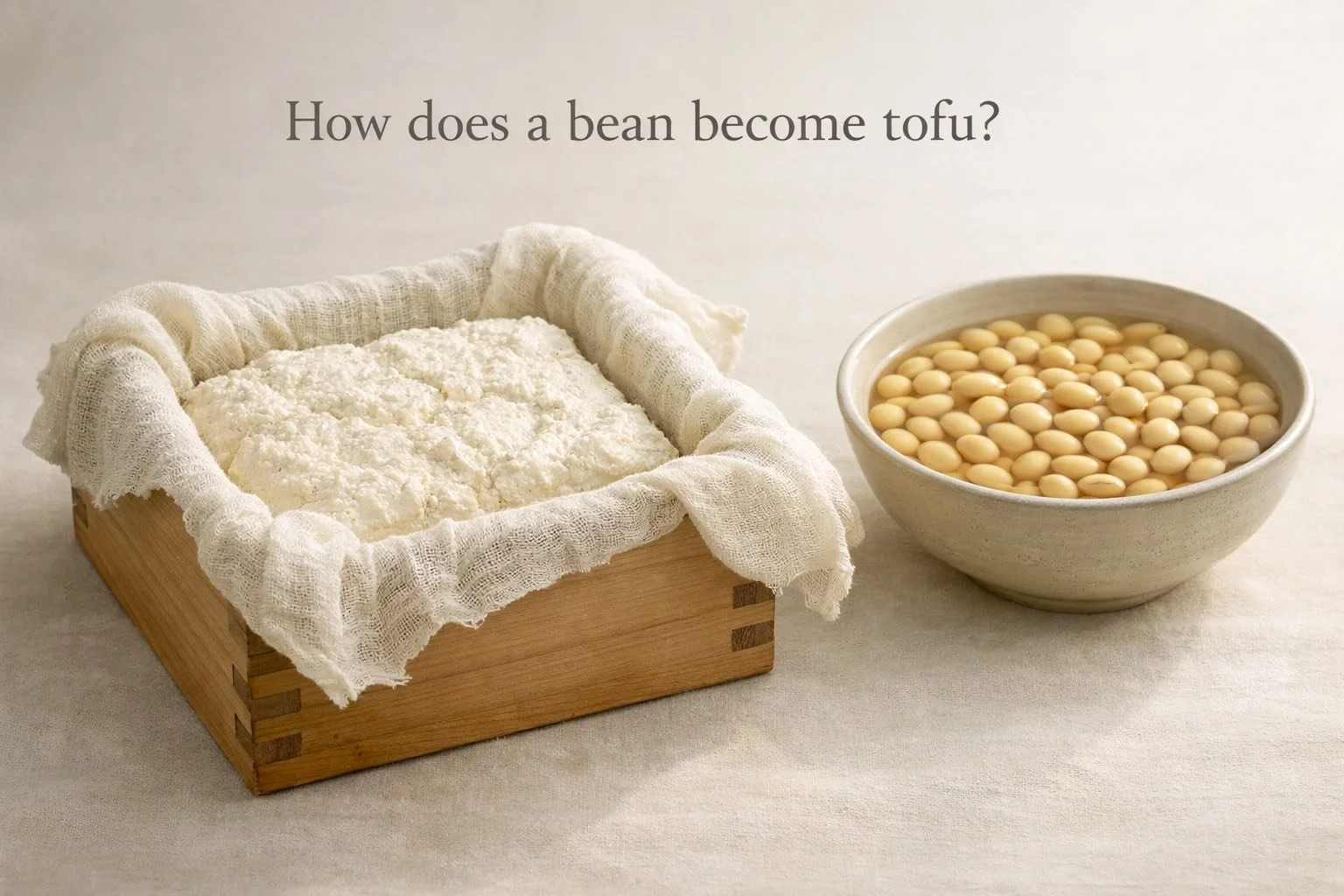

In many modern kitchens, tofu appears as a sealed white rectangle—quiet, uniform, and disconnected from its origins. But tofu is not an industrial invention. It is one of the world’s oldest crafted protein foods, shaped by touch, temperature, and timing.

Traditional tofu making sits somewhere between cooking and cheesemaking. It relies on a few ingredients—soybeans, water, and a coagulant—but demands attentiveness. Every step affects texture, flavour, and structure. When tofu is treated as a process rather than a product, it reveals why it has endured for over two millennia.

Step 1: The Bean — Choosing the Foundation

Everything begins with soybeans. Not all beans are equal. Traditional tofu makers look for beans that are:

Fresh and fully matured

High in protein (not oil-heavy varieties)

Free from age-related oxidation

In regions like China and Japan, tofu makers historically selected beans from specific harvests, knowing that protein quality affects curd strength later.

The beans are soaked—often overnight—not to soften them for convenience, but to fully hydrate the protein matrix. Incomplete hydration leads to weak extraction and fragile curds.

This is the first quiet rule of tofu: structure begins long before curds appear.

Step 2: Grinding — Releasing the Protein

Once soaked, the beans are ground with water. Traditionally, this was done with stone mills, producing a thick, raw soy slurry.

Grinding isn’t about pulverising—it’s about liberation. The goal is to rupture cell walls so soy proteins can later dissolve into the liquid phase. Too coarse, and protein yield suffers. Too fine, and filtration becomes difficult.

What emerges is raw soy milk plus okara (soy pulp), still intertwined and full of potential.

Step 3: Cooking — Safety and Transformation

The raw slurry is heated and then filtered, separating smooth soy milk from fibrous okara. This cooking stage is critical.

Boiling the soy milk does three things:

Denatures proteins, making them responsive to coagulation

Neutralises anti-nutritional compounds

Develops subtle sweetness and aroma

Traditionally, tofu makers rely on sight, sound, and smell—not thermometers. The milk thickens slightly, the foam changes character, and the aroma shifts from grassy to nutty.

This is not rushed. Boiled too briefly, the tofu tastes raw. Boiled too aggressively, it scorches and weakens the structure.

Step 4: Coagulation — The Moment of Magic

Here, tofu is born.

A coagulant—most commonly nigari (magnesium chloride) or gypsum (calcium sulfate)—is added gently to hot soy milk. This causes dissolved proteins to unfold and link together, trapping water in a delicate gel.

This stage is not stirred like a sauce. It’s coaxed.

Traditional tofu makers often add coagulant in stages, watching how curds bloom beneath the surface. Too fast, and curds shatter. Too slow, and they never fully form.

What appears is not a solid block, but soft, cloud-like curds floating in whey.

This is tofu at its most alive.

Step 5: Resting — Letting Structure Set

Before pressing, curds rest.

This pause allows protein networks to stabilise naturally. Skipping or shortening this step leads to brittle tofu that leaks water later. Traditional makers understand that firmness comes from patience, not pressure.

The curds are then gently ladled into cloth-lined moulds—never poured aggressively.

Step 6: Pressing — Shaping Without Force

Pressing tofu is not about squeezing it dry. It’s about guiding excess water out while preserving internal structure.

Weights are light at first. The cloth supports the curd as it consolidates. Over time, pressure increases just enough to set the shape.

Different tofu styles emerge at this stage—but not all tofu is pressed in the same way:

Gentle pressing → soft tofu

Moderate pressing → firm everyday tofu

Extended pressing → dense, grill-ready blocks

In traditional workshops, pressing is adjusted by hand and intuition—not timers.

Step 7: Cooling and Storage — Preserving Freshness

Freshly pressed tofu is cooled in water. This halts structural tightening and protects the surface from drying.

Traditionally, tofu is stored submerged and sold the same day. Fresh tofu has a gentle sweetness, clean aroma, and supple bite that packaged versions rarely capture.

This is why tofu was historically a morning food—made at dawn, eaten by midday.

Why This Craft Still Matters

Understanding traditional tofu-making changes how we cook and eat tofu today.

It explains why:

Texture matters more than flavouring

Heat management is essential

Tofu rewards respect, not force

When we reconnect tofu to its origins, it stops being a substitute and becomes what it has always been: a thoughtfully engineered food built from nature, skill, and care.

A Final Thought from Tofu World 🌱

Tofu doesn’t ask us to abandon tradition—it invites us to remember it. Every block carries the memory of beans soaked, milk stirred, curds waited for.

When you cook tofu with intention, you’re not just making a meal. You’re continuing a quiet craft that has fed generations—one gentle step at a time.

Let’s tofu-fy the world, starting with understanding. ✨